When he channels his foreboding side, like on the beautifully ominous “Hail Mary,” the results are substantially more gratifying.

Just like “Me Against the World” and “All Eyez On Me,” the weakest links here are the volatile ones, like opener “Bomb First” and closer “Against All Odds,” both of which are nothing more than “shoot before you get shot” assaults upon his aforementioned enemies. Most of Tupac’s worst efforts showcased his desire to be all things gangsta, and this album is no different, with the exception of the rollicking outlaw anthem “Me and My Girlfriend,” a version that destroys Jay-Z’s sampling, (a curious event in itself as Jay-Z is referred to as a “corny sounding mother***er” on this record).

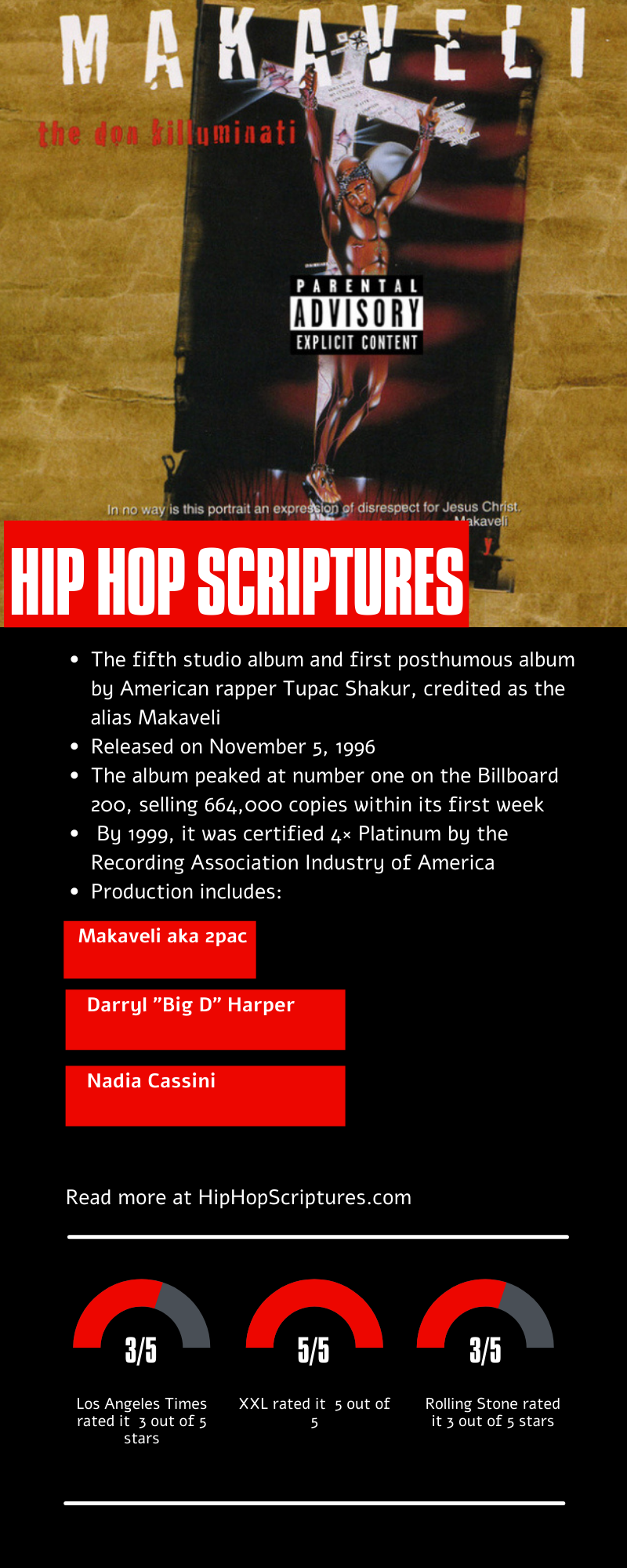

It’s difficult to decide which side truly encapsulated his personality, the most logical idea is that he was torn between all, yet his greatest successes were achieved when he jettisoned volatility in exchange for either sentimentality or vulnerably questioning his own demise. Tupac had several distinct lyrical personas, but the most consistent and prevalent are the chest puffing, live-by-the-sword thug, the introspective, nostalgic gentleman who wrote songs about the old school, the plight of young women, his mama, and the soothsaying, death obsessed paranoid. Daz, Dre, Snoop, and Nate Dogg weren’t walking through the door this time around, and the result is a dark, stripped down, at times introspective, at times attacking album that perfectly showcases Tupac’s bipolar duality. From an atmospheric standpoint, “The Don Killuminati” is a far cry from the bombastic, West Coast Rap defining party romp that was his previous release, “All Eyez On Me.” With the exception of stereotypical sex romp “Toss it Up” and the overtly nostalgic “To Live and Die in L.A.,” the album is awash in morose melodies, foregoing the sunny beats of the “California Love’s” “All About You’s” and “How Do You Want It’s” of yore. Looking back, it seems that Tupac’s obsession with resurrection and metamorphosis had a lot more to do with altering his artistic direction than an elaborate hoax to fake his own demise. What we failed to recognize at the time however, is “The Don Killuminati” was not a prophetic road map awash in clues of Tupac’s demise that distinction belongs to his masterpiece “Me Against the World.” When all hyperbole is removed and coincidences ignored, Tupac’s episode as Makaveli can be taken for what it truly is, a straight forward, above average hip hop album whose packaging and timeliness led us to believe it was something it ultimately was not. The record was an event, and the four million units moved inside of a year proved our insurmountable thirst for conspiracy. When Death Row decided to wait all of two months to release “The Don Killuminati,” a shameless act of contrived exploitation, great attention was paid to the depiction of Tupac plastered on the cross, and the inclusion of the eerie “exit Tupac, enter Makaveli” statement in the liner notes was viewed by some as Nostradamus-esque ponderings. The fact this recording incorporated numerous ideologies to the number seven, and seven days as a concept, an idea that is rooted in the notion of resurrection, is also a substantial coincidental quagmire. In the 13 year fallout and with the benefit of hindsight, it is safe to assume that Pac is no more, regardless if Suge Knight, a couple of Crips from Los Angeles, or Bugs Bunny was the evil genius behind his ghastly demise, but we didn’t want to believe it at the time.Īdmittedly the fact two months before his murder Tupac decided to record an album under the pseudonym Makaveli, an ode to a scheming political writer who advocated faking one’s death to beguile enemies is a notable coincidence and didn’t exactly quell the hysteria. We scoured the morbidly prophetic songs “Death Around The Corner,” “If I Die Tonight,” “Bury Me a G,” “Life Goes On,” and “How Long Will They Mourn Me” from past releases, bargaining that Tupac’s obsession with death was really all part of his evil plot to either avoid the law, or lull “enemies” like Mobb Deep, Nas, and Biggie Smalls into a false sense of security before an unpredictable and triumphant return to extract revenge. When ‘Pac got shot (for the second time), fans (like the 16 year old me), patiently waited for his return while tearing his discography apart for clues, grasping for unattainable straws of hope, worshipping at the desperate altar of denial. Denial was masked with intrigue, morbid curiosity supplanted logical thought, and no one wanted to admit Tupac was as dead as Kennedy. Owing to human nature’s incapability to resist anything shrouded in mystery, the 1996 death of Tupac Shakur set off a colossal wave of paranoia. Review Summary: Exit 2Pac, Enter Makaveli.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)